Written by: Samantha Burgess, editor-in-chief

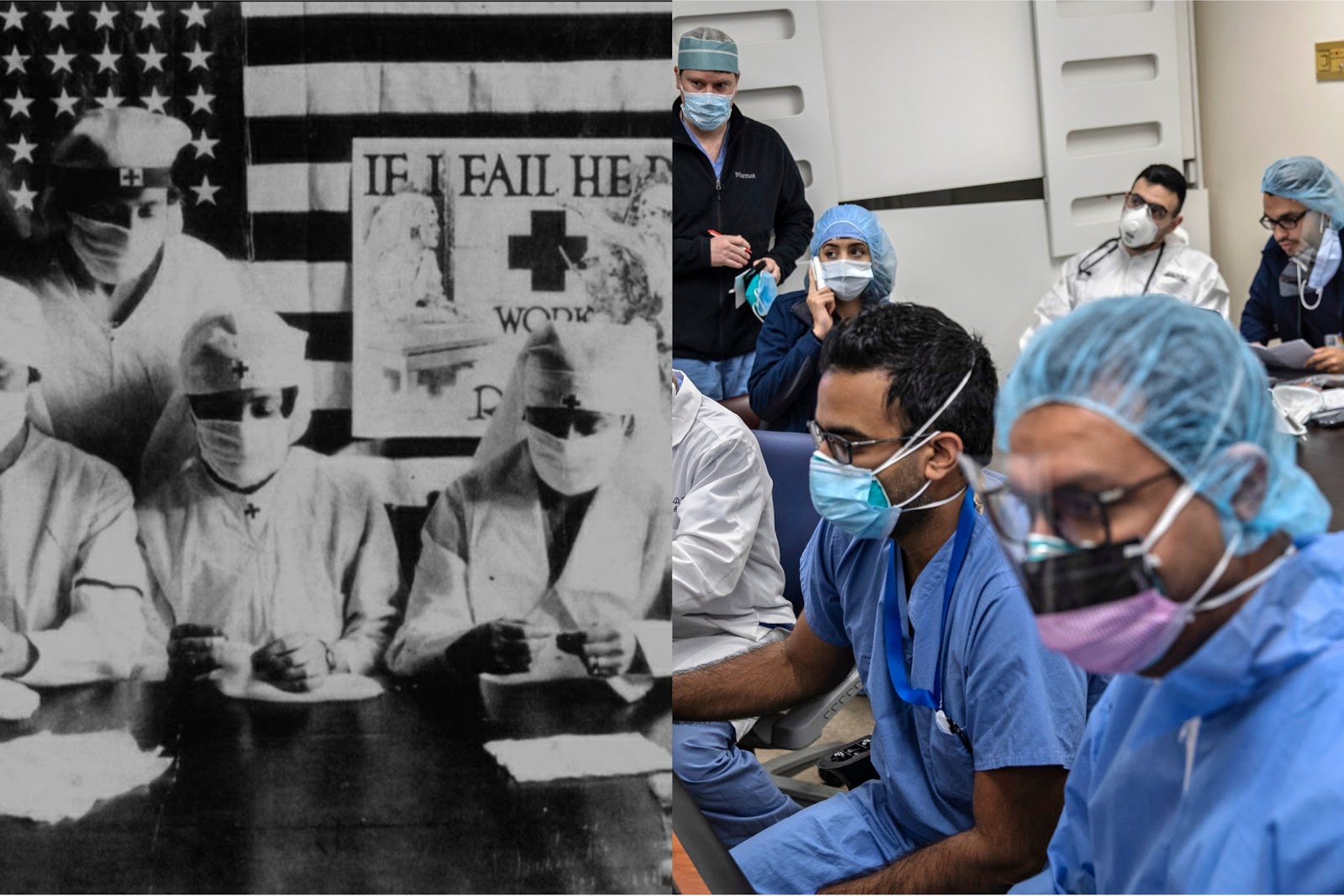

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn.—COVID-19 is the first worldwide pandemic that most of us have seen in our lifetime. No one could’ve predicted that we’d be forced to stay socially distanced or that in a span of a few months the number of COVID-19 cases worldwide would rise to over 2.6 million with 180,784 of those cases ending in death.

However, this isn’t the first time our country has faced a pandemic related to a ‘close contact’ virus. The Spanish flu, H1N1, SARS virus and MRSA virus all have similarities to COVID-19. But, how did we respond to these viruses compared to COVID-19? Which methods worked and what measures should we take now?

Beginning in March of 1918 and ending in December of 1920, the Spanish flu is considered the deadliest pandemic in modern history with at least 500,000,000 cases and 50,000,000 deaths worldwide (675,000 in the U.S.). The Spanish flu, also known as the H1N1 virus, spread through close human to human contact and symptoms were that of the typical flu we know today: chills, fever and fatigue, with recovery after several days.

The first reported American case was at a military base in Kansas in March of 1918, with other cases popping up in Philadelphia and St. Louis and then spreading across the country.

According to National Geographic, the Spanish flu did not see a dramatic decrease until social distancing measures were implemented.

After hosting a parade that resulted in 20,000 new cases, Philadelphia was one of the first cities to shut down by closing schools, churches, theaters and public gathering spaces on October 3. Cities such as St. Louis, San Francisco and New York quickly followed suit.

A 2007 study by the Journal of American Medical Association analyzed the death rates of the Spanish flu pandemic in 43 U.S. cities.

Two years later, studies from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences used this data to reveal that death rates were around 50 percent lower in cities that implemented preventative shut down orders early on, versus those that did so late or not at all. The most effective measures had simultaneously closed schools, churches, and theaters and banned all public gatherings.

The most recent pandemic (before COVID-19), occurring in 2009, is that of the H1N1 swine flu, which was a new strain of the original Spanish flu. H1N1 started in the spring of 2009 in Mexico and was declared a worldwide pandemic in June of 2009.

The CDC estimated 60.8 million cases of swine flu, with over 274,000 hospitalizations and nearly 12,500 deaths in the U.S. in April 2009-2010. H1N1 spreads through respiratory droplets and airborne particles with symptoms being the same as the original Spanish flu.

The majority of the 2009 flu pandemic affected children and young adults, with 80% of the deaths in people younger than 65. That is unusual for most strains of flu viruses, but in the case of the swine flu, older people seemed to have already built up immunity to the group of viruses that H1N1 belongs to and thus were largely unaffected.

The biggest difference in prevention between H1N1 and COVID-19 is that the U.S. was much more prepared for H1N1 thanks to data and treatments from the 1918 pandemic.

Within four weeks of detecting H1N1 in 2009, the CDC had begun releasing health supplies from their stockpile that could prevent and treat influenza, and most states in the U.S. had labs capable of diagnosing H1N1 without verification by a CDC test.

Another close contact virus that impacted America is the MRSA virus which was first discovered by British scientists in 1961.

MRSA is short for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a type of bacteria that is resistant to several antibiotics. It spreads through skin-to-skin contact and shared machines and medical devices. MRSA causes skin infection and in some cases pneumonia and/or sepsis.

MRSA saw peak outbreaks in the U.S. in 2008 and 2010 and has resulted in 120,000 cases and 20,000 deaths. The virus is still seeing cases with 5% of hospital patients contracting it. Despite this statistic, no serious preventative measures, such as those taken during the Spanish flu and current COVID-19 pandemic, were implemented.

MRSA is easily prevented by maintaining good hand and body hygiene, keeping cuts, scrapes, and wounds clean and covered until healed, avoiding sharing personal items such as towels and razors and getting care early if you think you might have an infection.

Another important but less deadly outbreak is that of the 2003 SARS virus. SARS, first reported in Asia in February of 2003, led to a total of 8,098 cases worldwide, 774 of which resulted in death.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus, called SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV). This virus is perhaps the most important to note as it relates to the current COVID-19 virus.

SARS spreads through close human to human contact, thought to be transmitted through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

SARS begins with a high fever (greater than 100.4°F) followed by other symptoms that might include headache, an overall feeling of discomfort and body aches. Some people also have mild respiratory symptoms at the outset. After 2 to 7 days, SARS patients may develop a dry cough and most patients develop pneumonia.

The current COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 virus, has totaled 2,603,147 cases world wide, with 180,784 deaths and 701,426 recovered.

Comparatively, while the virus spreads quickly, it’s current death rate (0.00694%) is lower than that of viruses such as the Spanish flu (10%), H1N1 (0.0208%), MRSA (16%) and SARS (9.2%)

According to the CDC, COVID-19 is thought to spread between people who are in close contact with one another (within roughly six feet) through respiratory droplets from an infected person’s coughs or sneezes. It’s also possible that a person can get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their own mouth, nose or eyes (this is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads).

COVID-19 may range from mild to severe symptoms of cough, fever and shortness of breath and, in worst-case scenarios, leads to severe pneumonia and organ failure. COVID-19 most commonly affects those 40 and older, although young adults are often asymptomatic carriers.

Despite the many similarities between SARS and COVID-19, they are considered different due to the fact that they originate from different types of coronavirus (The term “coronavirus” refers to a large group of viruses known to affect birds and mammals, including humans).

Furthermore, while both have similar symptoms, there are some differences. While both cause fever, cough, fatigue and shortness of breath, SARS alone causes malaise, body aches and pains, headache and occasional diarrhea and chills.

Also, while COVID-19 spreads more easily, mortality rate for COVID-19 is less than one percent whereas the mortality rate for SARS is 10 percent.

Additionally, the World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 5 (20 percent) of people with COVID-19 will need to be hospitalized for treatment, with a smaller percentage of that group needing mechanical ventilation. SARS cases, in comparison, were more severe with closer to 30 percent of people with SARS requiring hospitalization and mechanical ventilation.

“What was gratifying during the SARS outbreak is that there was unprecedented collaboration among scientists and laboratories around the world to work together to identify the causative agent, map its genome and develop reliable diagnostic tests.” said Dr. Shigeru Omi in his book SARS: how a global epidemic was stopped. “There was openness and willingness to share critical scientific information promptly. As a result, the virus responsible was identified and its genome mapped within weeks of the outbreak.”

Comparatively, COVID-19 has seen much less worldwide collaboration. The first cases appeared in Wuhan, China in 2019. According to President Trump, China downplayed the seriousness of the virus and neglected to share coding for the virus.

Trump also pointed blame towards the World Health Organization, referring to one of their Tweets which stated, “preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission [of COVID-19]”

Fox News also addressed that, despite Wuhan, China reporting that their cases had practically dissipated, new numbers suggest their COVID-19 death toll has actually risen by 50 percent.

Still, others argue that Trump ignored many of the virus’ warning signs and professionals such as Dr. Fauci stated that many more lives could’ve been saved had preventative measures been taken sooner.

Although it seems Dr. Fauci places blame on Trump, it should be noted that Newsmax addressed an interview they had with Dri. Fauci in January where he said that the virus was “not a major threat.”

However, pointing fingers will get us nowhere; we cannot change what has already happened. What we can do is implement successful past approaches to ‘close contact’ illness outbreaks in our approach to ending COVID-19 and flattening the curve.

One of the most important measures the U.S. can take right now is to collaborate with scientists and medical professionals worldwide in order to find a vaccine and/or treatment. This is evident in the swift response to SARS and the current H1N1 vaccine that is a direct result of the treatments that resulted from the Spanish flu pandemic. Americans can help by donating to organizations such as the World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control which fund research.

In addition, following the parameters of stay-at-home orders and social distancing helps prevent the spread of COVID-19. We learned from the Spanish flu how effective social distancing was in stopping the spread of the virus. We also saw with the Spanish flu, a second wave of cases after social distancing guidelines were eased.

Although none of the other pandemics saw a second wave of cases, it’s important that we follow social distancing guidelines in order to flatten the current COVID-19 curve.

Just as the original Spanish flu and SARS have no vaccine (and the current flu vaccine doesn’t fully prevent the flu), there are currently no vaccines or treatments for COVID-19, which would be the most effective approach to overcoming the virus, but there are several ongoing drug trials.

For other ways you can help during the COVID-19 pandemic check out my previous article.

*Note: parts of this article contain ideas and opinions from the author and are not a reflection of the views of the Triangle or Bryan College as a whole.

Samantha Burgess is a senior communication major with an emphasis in digital media and is editor in chief for the Triangle. Her interests in writing include profiles and feature articles. Burgess can often be found curled up with a good book, writing, listening to music or watching Netflix.